There is something especially evocative about quilts made from used clothing. For those of us whose families included quilters who made quilts for everyday use and who are lucky enough to have some of those quilts, these passed-down treasures more than likely include fabrics that had been repurposed from shirts, pants, dresses, aprons and the like worn by relatives.

Somehow, this knowledge adds an extra layer of appreciation for the quilt, regardless of how utilitarian or tattered it might be. Just knowing that those fabrics had a direct and intimate connection to another human being provides a resonance and a deeper connection to the quilt made from them.

Recently, quilts made from used clothing have taken on an additional meaning as a powerful vehicle for drawing attention to pressing social issues. One such effort is the The Migrant Quilt Project, which creates quilts from clothing and other personal textiles left behind in layup sites used by migrants for rest and shelter while travelling through the Sonoran Desert of Southern Arizona as a way of raising public awareness about the thousands of men, women, and children who have died trying to enter the United States to find a better life.

Another powerful example is the eviction quilts being created by James Matthews of Little Rock, Arkansas. Matthews is a multi-media documentary artist who is Director of Communications for the Episcopal Diocese of Arkansas.

For years, he has walked or biked around Little Rock, taking photos as he explores the city. Through a gallery he ran for several years, he shared things he created for exhibitions designed to help others gain a more nuanced perspective of Little Rock. For example, he mapped the history of violence in the city’s landscape; organized urban walks that followed the original 1831 boundaries of the city; and gathered clay from downtown building sites to make pottery.

As he traversed the city, he began noticing piles of clothing, furniture, and personal belongings stacked up on the curbs in front of houses. He asked neighbors in those areas why the items were there and discovered that it was the result of a person or family being evicted from a home. It was particularly troubling when he realized that a child was frequently part of the eviction, as evidenced by articles in the piles.

As a father himself (Matthews and his wife, an Episcopal priest, have three children), he was disturbed to realize that evictions especially affect women and children, and he knew that the problem was largely invisible to much of the community. He wanted to do something to raise awareness of the issue.

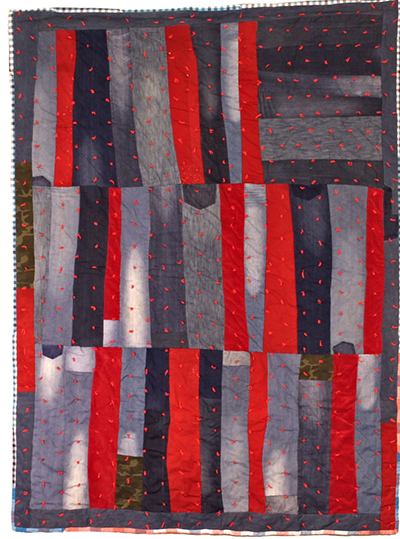

“I tried to photograph the aftermath of evictions, but it felt cold and distant,’’ Matthews says. “I’d see things like stuffed animals, a backpack with schoolbooks in it, and clothing from each of the members of the family. People could relate to clothing similar to what you might wear. It humanizes these objects and the eviction. That’s when I decided to make a quilt from fabrics I recovered from the eviction sites.”

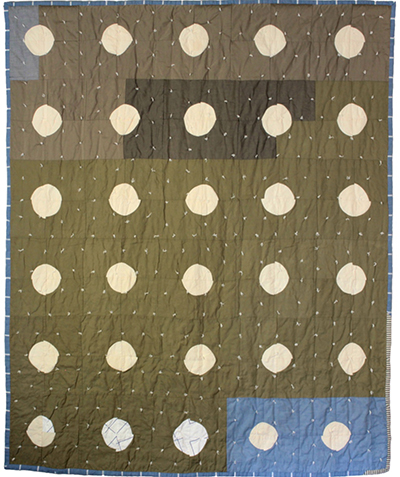

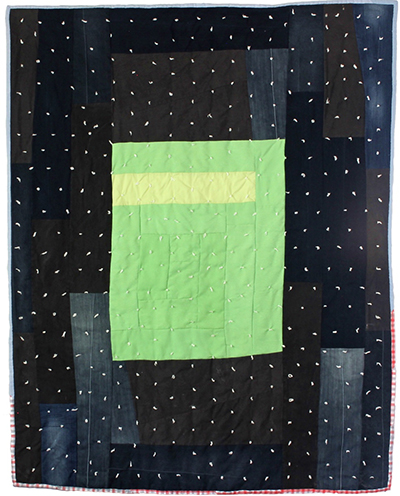

Matthews hoped that people might come back to collect their belongings, but after watching the sites and realizing that was not going to happen, he found out when the trash trucks ran in a particular neighborhood and waited until the last minute before picking up the leftover clothing and bedding. He brought the items home, washed and ironed them, cut them into pieces, and sorted them by color.

He had never made a quilt before and no one in his family made quilts, but he did know how to sew, having learned in order to make some things for his daughter. He holds a Certificate in Documentary Arts from Duke University’s Center for Documentary Studies and has also studied folklore in graduate school at the University of North Carolina and pottery at the Arkansas Arts Center. His folklore course had included a review of traditional quilting, so he was not entirely unfamiliar with the process.

After the first quilt made from textiles gathered at an eviction site garnered a lot of interest, he made others—and the eviction quilts are now a series of nine. Matthews titles each quilt after the name of the street where the fabrics used in it were found, and each quilt represents a single eviction. “Quilts speak of home, stability, history, tradition, and passing things down,” he says. “These eviction quilts are about the loss of those things.

“I thought the evictions were an important story to tell about Little Rock,” Matthews continues. “You are never far away from that idea that this material represents real lives and real losses for these people. You never want to lose sight of that. The material has been transformed into something that hopefully is looked upon as beautiful. It holds within it a tension: This beauty comes from tragedy. Without the knowledge the quilt came from an eviction, it loses most of the point. Divorced from the origin of the material itself, it loses its real purpose.”