Many of us are familiar with best-selling author Tracy Chevalier through her historical novels, including “Girl with a Pearl Earring”, which was made into an Oscar-nominated film. What you may not know about her is that she is a quilter.

Tracy, who was born in the United States but who resides in England with her husband and son, learned how to quilt as part of her preparation for writing her pre-Civil War-era novel, The Last Runaway, about an English Quaker woman who gets involved in the Underground Railroad helping slaves escape to freedom. In order to write authentically about quilting, which is an element of her story, she decided to take a class and learn how to do it herself. As frequently happens to many people, she got “hooked,” and started making quilts of her own.

Following the publication of The Last Runaway, Tracy was approached by Caroline Wilkinson of the British prison charity organization, Fine Cell Work, to talk about the book and her quilts with a group of prisoners. Working with Great Britain’s leading contemporary designers, Fine Cell Work teaches inmates to make high-quality, handmade needlework items for sale to the public in order to boost prisoners’ self-worth and provide skills to help them live crime-free lives upon their release.

She accepted the invitation with some trepidation, not knowing what to expect, but when she met with the inmates—all of whom were men—she was quickly set at ease. Impressed with their interest and skills, she had an idea.

She was at that same time also curating a quilt show she called “Things We Do in Bed” to be exhibited in five bedrooms of a Georgian mansion in London. In each of the rooms, Tracy’s concept was to display quilts related to a different bedroom activity: birth, death, sleep, sex, illness, and death. She decided to ask the prisoners if they would make a quilt specifically for her exhibit.

“Of the five themes of the show, sleep seemed to be the more appropriate and less controversial for prisoners,” Tracy explains. “The need for sleep is universal, and I assumed, a kind of comfort in prison. And so the Sleep Quilt was born.”

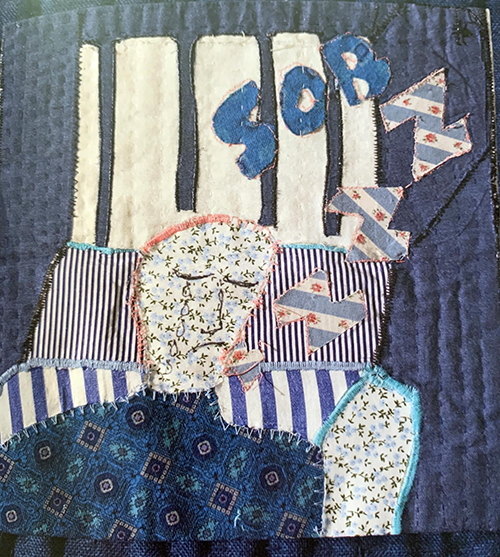

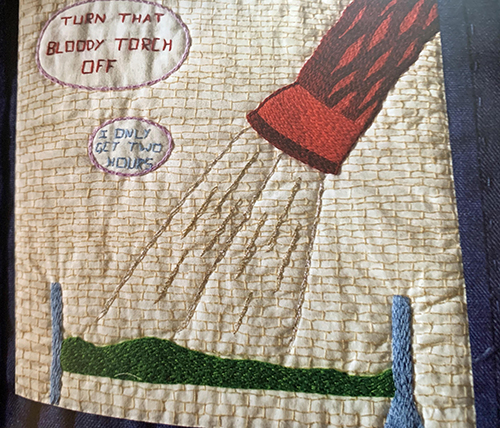

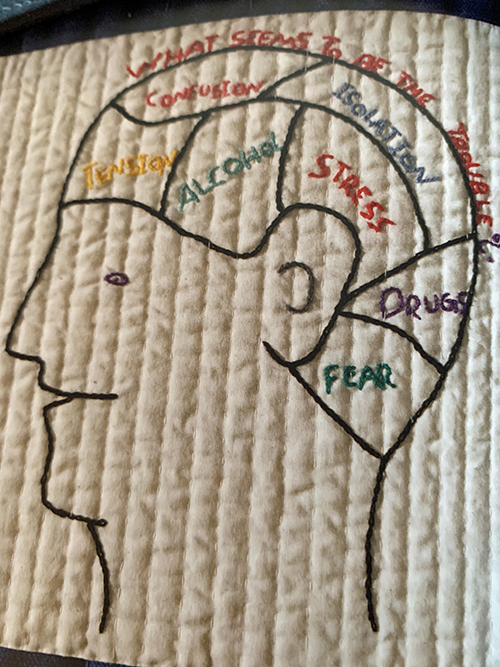

Tracy invited those wanting to participate to design and decorate a 10-inch (24.5 cm) square of cream-colored fabric with images or text or both using embroidery and other fabrics in order to illustrate their own feelings about sleep. The prisoners associated with Fine Cell Work are accustomed to working on projects designed by someone else, so it was unusual for them to be asked to create something original—especially anything that would require them to produce a personal expression about an aspect of prison life.

She asked them questions: “How do you sleep in prison? Well? Poorly? Do you sleep more or less than you did outside? What are your dreams like? Have they changed since you’ve been inside? Are they happy or do you have more nightmares?” And so on.

“It turns out that sleep is not so benign a topic in prison as I’d thought,” Tracy continues. “A lot of inmates sleep poorly. Prisons are often hot, poorly ventilated, and noisy. Inmates are often sharing a small cell with someone they don’t know well or may not like. There’s also plenty of time just to lie there and think about the bad decisions they’ve made, the people they’ve let down.”

After eight months of work, the prisoners responded with remarkably creative and personal squares that were assembled into a 9’ x 7’ (275 X 215 cm) quilt. In 2014, it was displayed on a real prison bed in one of the rooms for the “The Things We Do in Bed” exhibit. Thousands of people saw it and were profoundly moved by it.

Since then, the Sleep Quilt has been exhibited in many other places to universal acclaim and interest. The quilt was so popular that a book has been made about it*. And as for the prisoner-artists, they, too, were moved and changed by the experience, saying that they were grateful to have had an outlet to express themselves and to make something meaningful with others. They are proud of the way the public has received it.

The term “meta” has come to mean something self-referential. Since quilts were traditionally made to be slept under, Tracy’s idea of making a quilt about sleep is about as meta as it gets. This idea is further reflected in a block for the Sleep Quilt made by one of the prisoner-artists that illustrates a sheep counting sheep in order to go to sleep. This clever self-awareness just adds to the quilt’s overall appeal.

Those of us who love quilts are not surprised by the extraordinary ability of a quilt and its creation to be so much more than the sum of its parts. Tracy Chevalier captured this truth beautifully when she was described the composition of a quilt.

“But there are two other, unseen layers. There is the physical imprint of the maker: every centimetre of a quilt will have been touched by them, absorbing literally blood, sweat, tears, skin, hair, oil. And there is the emotional layer, the history of the maker absorbed into the making. A quilt can take a long time to complete, especially when hand-made. It is there with you as you laugh and cry and shout and gossip. It seems to me that all of that enters the quilt, imbuing it with an almost talismanic quality.”

*The Sleep Quilt, a book about the project, by Tracy Chevalier and Fine Cell Work, is available from Pallas Athene (Publishers) Ltd. and also from Amazon.